Specifically, they issued a Master/Local Control Center Procedure No. 2, which asks all generators and loads to immediately cease testing and maintenance and be ready to generate power, so as to “not further jeopardize the reliability of the power system”[2]. It was New England's cry for help.

The odd thing is that December 4th was a relatively unremarkable day. At 40 degrees Fahrenheit, with no precipitation and little wind, there’s no immediately clear reason for New England’s sudden distress. The New York Independent System Operator saw similar price jumps- sliding suddenly from $36 to $-160 dollars per MWh, and then climbing to over $1000 in a matter of minutes[3]. Ontario’s zonal prices both exploded and crashed, indicating large-scale transmission issues[4]. Whatever was eating at New England’s grid was affecting its neighbors, too. Something was clearly awry in the Northeast, and system operators were acting quickly to compensate.

Chart above: Wholesale electricity prices in New England's Henry Hub and New York's North zone[1][3].Ontario realtime prices are were not available in data archives.

First, a little background: New England, New York, and Ontario all have structures in place called Independent System Operators, or ISOs (sometimes called RTOs). These are non-profit organizations dedicated to an open electricity market with a strict emphasis on reliability. They do not generate, buy, or sell electricity, but they are in charge of transmission, and their primary goal is to ensure that energy gets where it needs to in a fair and reasonable way. Think similarly to Wall Street for electricity- in the same way that Wall Street needs to ensure that the money from every trade is processed safely and effectively, ISOs ensure that electricity is bought sold, and delivered with no interruptions. Simply put, ISOs are there to ensure that the lights stay on.

There are several ISOs across North America. As open market systems, they provide a reliable structure into which power generators bid in. It's a supply and demand world out there, and as additional generation is needed, ISOs raise the price of electricity, and generators who bid into the market the day ahead are required to come online. A price spike, such as the one seen on December 4th, is indicative of a severe electric supply shortage.

|

| Map of North American ISOs. Note- as of October 2013, the New Brunswick System Operator (NBSO) has been disbanded. |

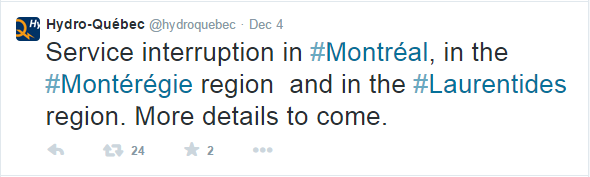

ISOs also have a dedication to releasing some amount of public data, a requirement that independent utilities are not subject to. This means that for New England (ISO-NE), New York (NYISO), and Ontario (IESO), pricing and market data is easy to come by. So how do we find out what happened? The data we're getting from the regional ISOs shows their distress, but not the source of it. In the age of information technology, however, one source of breaking news stands out among the rest: Twitter.

Hydro Quebec is not an independent system operator, but instead a private utility company that controls generation and distribution of electricity throughout Quebec. Quebec is the Canadian province just above New England, and is a region prolific for it’s hydroelectricity which it exports almost continuously. They do not release public data on their markets.

Secondly, the outage relates to two lines on the transmission grid. This doesn't mean that a tree fell on a local power line somewhere- the electricity lines you see along the street and outside your house aren't part of the transmission grid, they’re part of the distribution network. The transmission grid is the set of massive high-voltage lines that connect whole power plants to whole cities and towns- lines like these:

|

| Typical transmission lines |

Having an outage on a transmission line is bad- really bad. We have talked earlier about how maintaining frequency on the grid is important, and transmission lines help regulate frequency in a big way. Once a transmission line goes down unexpectedly, it can disconnect your generation from your load- which means you have a frequency problem on both sides of the downed line. Not only does this cut power to whatever you were powering, but it trips off generation, causing the power plant to shut down in order to protect itself from the resulting power surge.

Once Hydro Quebec saw their transmission lines dropping, they started to worry a lot. They needed to maintain the parts of the grid they still had up, so they quickly slashed power exports to all of their surrounding regions. This was a huge problem for the neighboring ISOs, long used to propping up their electricity demand with Quebec’s hydropower.

And so New York, New England, and Ontario turned inward and fired up their most expensive peaker power plants to make up the difference. ISO-New England, which lost a full 1,500 MW of imported power in a matter of minutes, had to increase their price 50-fold in order to activate their emergency peaker power plants.

But Hydro Quebec soon found the problem widening. Less than an hour later, they had already dropped more customers offline:

This was no longer a problem just for Quebec. With the blackout spreading, the surrounding regions knew that they needed to prevent the issues from escalating. So, all three regions turned the power around and sent their scarce energy back towards Quebec to stabilize the situation:

Chart Above: Average hourly electricity imports and exports from Hydro Quebec. A positive value denotes electricity exports from Quebec, negative value denotes electricity imports to Quebec.[1][3][4]

In two hours, the flow of electricity flipped nearly 5 Gigawatts- almost 25% of New England's typical peak load. For nearly 28 hours, all three ISOs delivered power to Hydro Quebec as it made a slow recovery. Quebec rerouted power, regained control of shut down equipment, and slowly restored power to Montreal and the other affected areas. By 10 PM on December 5th, Quebec had returned to a normal state.

This is a unique example of regional co-operation bringing the power grid back from the brink. This near-failure is both an example of how the grid is intended to deal with unexpected catastrophes, as well as how vulnerable it can be. Quebec didn't see this issue coming, and a month later said that the cause was still unclear[6]. But the regional response was effective and successfully limited the issue in a manner which grid operators were unable to do in 2003. In the end, this crisis hardly made the news- but just barely. If system operators had slipped up even slightly- this could have been a different story.

And for now, the grid goes on as usual, having fully recovered in a matter of days. Undoubtedly, more unexpected problems like this will arise, and we can only hope that grid operators are able to respond as quickly and effectively as they were on December 4th.

Sources:

[1] ISO-New England. Preliminary Five-Minute Real-Time LMPs. 01/28/2015.

[2] ISO-New England. Master and Local Control Center Procedures. 01/31/2015.

[3] NYISO. Pricing Data. 01/30/2015.

[4] Independent Electricity System Operator. Data Directory. 01/30/2015.

[5] Scientific American. The 2003 Northeast Blackout- Five Years Later. 08/13/2008.

[6] Concord Monitor. Widespread Hydro Quebec Outage Fuels Concern Over Future Reliability in N.H.. 12/27/2014.